OIL INDUSTRY FOLKLORE

Just published in the 2006 issue of the Petroleum History Institute's OIL-INDUSTRY HISTORY:

A BRIEF SUMMARY OF OIL INDUSTRY FOLKLORE

by Herman K. Trabish

- ABSTRACT: Sometime in the late nineteenth century, There’s GOLD in them thar hills!” transmuted into There’s OIL out there! As the oilfield pioneers left the Pennsylvania and Baku regions and took the industry to the farthest corners of the world, they created their own legends and lore. The premier chronicler of oil’s lore was historian and folklorist Mody Coggin Boatright. Building on field research which recorded the realities of oilfield life, he documented the tales that grew around the realities and how they grew taller as time passed. If not every well came in, each had its story. Real people transmuted into indelible character types. Finally, the real life of Gilbert Morgan of Callensburg, Clarion County, Pennsylvania, gave forth Gib Morgan, the greatest oil industry hero of them all.

- INTRODUCTION

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, There’s GOLD in them thar hills! became There’s OIL out there! Dreams of success turned ordinary men into oilmen ready to roam where ever they thought they might find a producing well. There is a tale about an oilman who arrives at a small isolated town where there is an oil boom. It might be Texas or California or Sumatra. He can find no accommodations. Not wanting to sleep outside, he begins making the rounds of the public houses, asking everyone if they have heard about the strike elsewhere. Eventually, his invented rumor takes hold and he encounters men who ask him about the elsewhere strike. By midnight the public houses are clearing and there is a lot of traffic leaving town. Accommodations become available. But our oilman does not take a room. Unable to resist even his own invented rumor, he is off to see about the strike elsewhere.

Eventually, that story turned into one about an oilman who, on dying and going to heaven, is told by Saint Peter at the Heavenly Gates that he will have to go to Purgatory and wait because all the oilmen’s places in Heaven are filled. The oilman smiles sadly and accepts this dictate but requests and is granted temporary admission for a visit with his friends. While chatting with the oilmen in Heaven, he casually mentions rumors of oil discoveries in Purgatory. Soon, his invented rumor spreads and eventually comes back to him. He notices movement in the crowd and, then, space clearing. Finally, he decides it is time to move on. At the Pearly Gates, he meets Saint Peter, who tells him there is now room for him. Sorry, the oilman says, I’ve heard a rumor and I think I’ll go Downstairs and explore. (Boatright 1963, p. 196).

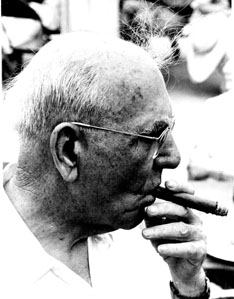

As the oilfield pioneers left the Pennsylvania and Baku regions and took the industry to the farthest corners of the world, they created their own legends and lore. The premier chronicler of oil’s lore was historian and folklorist Mody Coggin Boatright (Fig. 1) of the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Folklore Society. He built on field research done in the 1920s and 1930s by numerous folklorists and colleagues. They took notes and audio taped the recollections of men who had worked the oilfields all the way back to the days of Colonel Drake. Amid a storehouse of oilfield tales, characters, themes, types and lore, Boatright found and chronicled oil’s greatest hero, Gib Morgan (Fig. 2). He called the Gib Morgan folklore:

…equal to the best in the Crockett Almanacs and superior to the best in the Paul Bunyan legend. This lore, richly imaginative and often satirical, is known…wherever oil is produced in the United States. It is known…wherever American oil crews and technicians have gone. (Speck 1973, p. 62).

- In the Gib Morgan lore, oil region humor was transmuted...

- I. THE MYTH, THE TALL TALES, AND THE STORIES

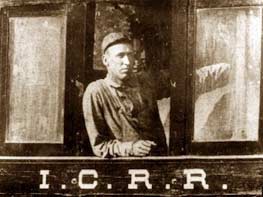

According to Boatright, a myth in very general terms may be taken to be a story whether true or not that is …associated with the most cherished values of the believers. (Speck 1973, p. 108). The singular myth of the oil industry, around which all the others grew, was the myth of the man and his well. Remarkably, it was sometimes a true story. After many retellings, it was essentially the same story, whether told of Drake in Titusville (Fig. 3), of Patillo Huggins (Fig. 4) and Captain Lucas at Spindletop (Fig. 5), D’arcy in Persia (Fig. 6) or Dad Joiner (Fig. 7) in East Texas: An unlikely man falls into a search for oil. (Drake was a retired train conductor drafted because he had a free railroad pass. Huggins was a Sunday school teacher who observed gas vents on picnics. D’arcy (Brice 2004) was a patriotic gold miner drafted into the service of Great Britain. Dad Joiner was a gigolo.) Fate taps the man on the shoulder. He becomes convinced and then obsessed, yet he finds no oil. Time and funds are expended. Those who hold the power and the purse call off the search. Just past the eleventh hour, the obsessed hero brings home the gusher. It is the stuff of melodrama, but it really happened, in Pennsylvania, in Texas, in Persia and in oil country all over the world. Tales grew around these realities and they grew taller as time passed. Indelible character types were born: the Geologist and the Doodlebugologist, the Promoter-Trickster, the brave Shooter, the cowboy Driller, the newly rich Landowner, the Oil Field Dove. And from the real life of Gilbert Morgan of Callensburg, Clarion County, Pennsylvania, came the greatest oil industry Hero of them all.

Tall tales often begin as jokes and often these jokes remain in the tale. An example would be an episode from Texas tall tale character Pecos Bill’s infancy...

Two favorite excerpts:

1.

Long after the originator of the Gib Morgan stories had died, journalist Harry Botsford heard a modern-day Gid Morgan in a bar telling a yet wilder tall tale. This Gid allows his female canary, Jen, to escape and mate with a bumblebee …almost as big as a hummin’bird… For a while there are no consequences.

Then the wells started to go dry, alarmingly. One day I heard buzzing and the beating of thousands of wings. There they was—whickles, thousands of them. A whickle is a cross between a bumblebee and a canary. Two divisions of the critters was streaming out of the casing head of an old well. Then I remembered my history. Whickles, unlike birds or insects, live on oil, and that was why the wells had been goin’ dry. Fact! They had been sippin’ thousands of barrels of oil right out from under our noses.

He spots the canary and the bumblebee, remembers Jen’s fondness for applejack and spills some, trying to lure them to capture. They escape. That night six horses, three cows and a travelin’ evangelist was stang to death. He goes to Harrisburg, gets a bounty put on whickles and sets out to

…save this great industry from further depredations of these dastardly whickles…All I need is a gallon of applejack, which I sprinkle on the bushes. As a rule, I get a dozen or so whickles. Of course, I lose some of the applejack. I scalp the whickles and mail the scalps to the governor, and right now he owes me round eighty thousand dollars. (Botsford 1942, p. 72)

This may or may not constitute real literature. …[T]he westward-moving men of action, Boatright wrote, unhampered by any high-falutin' theories of art, created their own literature. (Speck 1973, p. 70). If what we find in what comes down to us of oil industry humor and legend is not a sophisticated literature, it is a kind of lore. Like the pioneers before them, the early oilmen were primarily interested in the facts surrounding them. The shortcomings of the stories were due less to mean-spiritedness than to self-centeredness. As an academic, Boatright wrote books and essays, as have others, finely defining mythology, folklore and legend. But he left no doubt that there was something intrinsically valuable in what his research discovered. Each occupation he observed, has its lore—partly belief, partly custom, partly skills—expressed in anecdotes, sagas, tales and the like…Our culture is the richer for this… (Speck 1973, p. 118-19).

2.

The Tales Move West

The boomtowns in Texas, Oklahoma, California and around the world after the turn of the century gave a new flavor to oil industry legend and lore. Each of the great booms had its own circumstances, its own personalities, its own distinctive

impact, Ruth Sheldon Knowles wrote. (Knowles 1978, p. 120). But the makeshift towns where they boomed had many similarities. They were tough, rugged places, famous for a plenitude of hard drink, bad water, muddy oily streets, few toilets and fewer rentable places to sleep. And the stories moved from town to town with the men and the booms.

In the absence of law and order, oilmen made their own justice and told stories about it. W. H. (Bill) Bryant told a tale of boomtown justice when remembering a saloon that incurred the wrath of the oilfield workers:

If they could get your money, they’d get you drunk…So then we got tired of that. There was a railroad running beside of it where they hauled logs. And one night we got a bailing line and put it around it and put a clamp on it, and when the log train come by, we hooked it on to the log train and scattered that slab saloon about four hundred yards right down the railroad track. That’s the way we tore that one up, because it was trimming the roughnecks. (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 71).

Batson, Texas, undertaker Plummer M. Barfield remembered a grimmer instance of boomtown justice:

It was dark and had been raining…There was a roughneck killed in the field. I forgot now how…I went in the field and loaded the body…halfway back, why I met a bunch of men with lanterns…Says, ‘Well, throw him out. We got some more work for you to do.’ Well…there was a dead woman and a baby. I loaded them up and went on and unloaded them…

About the time I got that done, why, a couple of roughnecks come in and…says, ‘you can go back down there in the bushes about one hundred yards from where you were and…you’ll find two more.’

…And in the meantime I’d learned why there were two more down there. This lady’s baby had taken sick, and she’d got up to give it a dose of medicine or tend to it, and some rattlebrain drunks shot at the light, see, through the tent. Killed her and the child both. And these roughnecks and rig runners around there, they caught those two guys and hung them to a sweet gum tree. And them was the two men I went back and got… (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 75).

And don't miss this:

- 6. The Oil-Field Doves: There were few examples of women doing actual production work:

If it was, reported oilman H.C. Sloop, it was only an isolated case of a woman coming on the job to help her husband when he wanted to go to rest…I remember one or two women who ran boilers. But their husbands were working, running these boilers, and the women folks would come down and bring him lunch or bring him a change of clothing or something of that kind. And they had been there often enough for him to tell them how to handle the boiler and how to look after it. And he could go home and lie down…And outside of that I don’t know of anything. (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 113).

You’d have what you called these oil-field doves—the gals that hung around the oil fields, recalled oilman Landon Haynes Cullum, and there was plenty of them around…there were really some woolies, and they had all kinds of names for them. Some of them wouldn’t be very good to repeat. (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 162).

One female name that was repeated so often it became a slang expression was Ruby Darby. She began in a Dallas chorus line, honed her act in World War I army camps and made her mark as one of the first to sing the blues in the southwest boomtowns. Known in the 1920s as the toast of the oil-field workers, this brazen sensuous showgirl toured the oil camps in a big red flashy chauffeur-driven automobile, coming in wearing only a fur coat and a smile to guarantee a packed house for the night’s performance. Her trademark song was W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues but more popular than her sultry voice was her exotic dancing. They said she would strip at the drop of a driller’s hat; had ridden a hoss completely nekkid down the mud- and oil-splashed streets of Keifer, and had danced bare-skinned on a tool shack roof as men tossed silver dollars at her feet. She packed a pistol, wore silk stockings and would try anything once… and an acquaintance called her a natural adventurer. There was a popular couplet warning, If you’ve got a good man keep him home tonight/for Ruby Darby’s in town and she’s your daddy’s delight. (Wallis 1988, p. 187).

She was so highly loved in some of the Oklahoma oilfields that when a gusher came in the men would call it a Ruby Darby. Eventually, to call something a Darb was to say it could get no higher praise. In Ernest Hemingway’s (Fig. 14) The Sun Also Rises, the main character suggests his companion has some excellent acquaintances: You’ve got some fine ones yourself. The listener agrees that his acquaintances are good ones. Oh, yes. I’ve got some darbs. (Hemingway 1926, p. 107).

As Cullum pointed out, not all the women in the camps were so highly thought of, though many were respected for unique qualities:

There were women of every type, all types, from the smallest to the largest, and from the tenderest to the toughest, and we had lots of fighting among the women; of course, I don’t remember any women getting killed, recalled W.H. (Bill) Bryant. They generally got beat up, somebody would separate them. I believe Nella Dale and Grace Ashley put on the best bout I ever seen. I think they fought an hour and fifteen minutes before they were separated. And when they quit fighting they didn’t have on enough clothes to wipe out a twenty-two.

This fight taken place here in Sour Lake, and that woman was the best fighter I ever saw. I never did know what her real name was. We called her ‘Mooch.’ And she was from Cripple Creek, Colorado, and she was kind of every man’s pet hero because she could always come out under her own power when she was drinking, and she was a good fist fighter. (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 70).

…And I want to tell you something, Bryant was elsewhere quoted, the best hearts I have seen in people is in the underworld. I seen prostitutes after they commit suicide and maybe the girl didn’t have anything much. I’ve seen the other women take off their diamond rings and sell them…and help bury this particular woman…some of the women were taking care of their mother back home, and some of them was probably taking care of a baby where a sorry husband had walked out on them, and when you get right down she had a clean heart…some of them was tough as a boot and don’t you think they wasn’t. Some of them would pick your pocket, and they were just as low as they ever got, and others had lots of pride left. Now I know one woman—she was a fine-looking woman and she killed her husband and later married a field man. That woman straightened out and I believe she lived a clean life from then on. (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 118).

Oilman Frank Hamilton remembered more about Mooch:

Mooch was a gambler’s—supposed to be his wife. She’d sit up there with him at all times…And a low bunch was following so that you had to watch them. But this Mooch…was very pretty at the time that I first saw her in Sour Lake, Texas…The reason she got that name…was because if any roughneck or pipe liner would get sick, didn’t have any money, anything like that, why she’d go out and mooch all the oilmen…if a boy got sick or anything, why Mooch would start out. Wouldn’t be long until she’d have a quack doctor there, medicine, and plenty to eat.

Well, Mooch, she died in jail in Shreveport, Louisiana…She had a heart—a big heart—so they give her a respectful good burial… (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 118)

Corsicana boomtown veteran Carl F. Mirus thought Bob from Fort Worth got it right when he told an attorney from Corsicana who confirmed to Bob that the respectable Fort Worth woman he had married had indeed been a prostitute in Corsicana:

‘Well,’ he says, ‘you know people talk about me marrying a whore.’ Says, ‘I think it’s something to be proud of.’ He said, ‘Any man can go out with a girl that’s never been married and never had a sweetheart and persuade her to marry him, but,’ he says, ‘you take a man that takes a girl that has had ten thousand sweethearts and gets her to pick him out of all the rest and marry him,’ says, ‘now that’s really doing something.’ (Boatright and Owens 1970, p. 119).

In any pantheon of oil industry angels, a special place must go to Daisy Bradford and the many women who wittingly or otherwise funded Dad Joiner’s drilling venture. Joiner, it is said, obtained investments by reading the newspaper obituaries and courting widows of means. Using their money, Joiner drilled, on Ms. Bradford’s farm in 1931, the first well in what became known as the East Texas Black Giant. Playing the other side of the fence were the psychics and fortune tellers always in and around the boomtown camps, such as Zara of Beaumont, Madame Virginia of Abilene and Annie Jackson of Mexia. These were women who, like Dad Joiner, used what they had of insight and persuasiveness to induce oilmen to share their wealth.

Contributing to legend and lore in ways that require separate research essays were two other women. Ida Tarbell (Fig. 15) was a journalist and novelist who grew up in the mid- and late nineteenth century Pennsylvania oil regions, the daughter of an unsuccessful wildcatter. Ms. Tarbell was among the progressive journalists at McClure’s Magazine dubbed muckrakers by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906. Perhaps motivated by her father’s failure or perhaps by what she saw around her, Ms. Tarbell wrote a series of articles for McClure’s in 1902-03 which eventually became The History of the Standard Oil Company, published in book form in 1904. It was instrumental in rallying public and political sentiment for the legal reorganization of Standard Oil in 1911. Arguably, Daniel Yergin wrote, it was the single most influential book on business ever published in the United States. (Yergin 1991/92, p. 105).

Lydia Bragatouni (a.k.a. Lydia Pavlova) was another kind of woman entirely. A White Russian princess living in post-World War I Paris and working with other anti-Leninists to take back control of her country, she became a mistress of both Royal Dutch/Shell’s Henri Deterding and Turkish Petroleum’s Calouste Gulbenkian. She was perhaps the only neutral ground as these men wrestled for control of Mesopotamian oil in the 1920s. Eventually, as her political hopes faded, she rejected Gulbenkian and became Mrs. Deterding. Though the men reached a Red Line Agreement in Mesopotamia, there remained ever after a personal enmity between them over Lydia Pavlova. As Mrs. Deterding, she inspired a strong anti-Communist stance at Royal Dutch/Shell. (Yergin 1991/92, pp. 202 & 242).

Women essentially do not appear in the Gib Morgan tales...

- III GIB MORGAN

Paul Bunyan (Fig. 16), Pecos Bill (Fig. 17 and Davy Crockett (Fig. 18) are today thought of as Disney characters but they came out of regional oral traditions and lived for decades before Disney. They probably emerged into the national consciousness because academic chronicles in the 1920s bridged their passage into the popular media that emerged in that same period. Because they did transition

from folklore to Disney, they remain famous. As chronicled in Boatright’s work, Gib Morgan was to the oil industry what Crockett was to the frontier, what Bunyan was to logging, what John Henry was to railroad building, what Casey Jones was to railroading and what Pecos Bill was to cattlemen. Because post-World War I academics did not bring the Gib Morgan oral tradition into print in that era, it was not widely heralded and remains folklore almost forgotten to today’s popular culture.

Boatright, who died in 1970, described the tall tale as a kind of everyday art. He went to great lengths to precisely define tall tales with academic rigor. Gilbert Morgan was merely a practitioner of tale telling. As Boatright wrote in the The Art of Tall Lying …[I]n any group there will be those who know a good story when they hear one, and are not too strictly bound by facts to alter them if it makes the story better… (Speck 1973, p. 105). In the same essay, Boatright used the example of a character called Pie Biter to show how the Gib Morgan tall tales grew out of a familiar frontier style of storytelling. Pie Biter really was a Texas ranch cook named Jim Baker who won a bet by stacking five pies and eating them. Eventually, tales made Pie-Biter a cook for the Texas Rangers who could not only hunt buffalo from his chuck wagon, but also, in the absence of kindling, chase down prairie wildfires to cook the buffalo meat (Speck 1973, p. 78).

- The Real Gib Morgan

The real Gilbert Morgan was born July 14, 1842, in Callensburg, Clarion County, in western Pennsylvania...

They used to say that he was ‘the biggest liar in the oil country.’ I don’t think this is the proper title for him. I would say that ‘the best entertainer in the oil country’ would have been a much better title. (GM, #36).

Even in his last decade, he was able to obtain room, board and drinks at inns where he stayed with his entertaining, imaginative tall tales.

- The Tales of Gib

Gilbert Morgan’s hero, Gib, was a practical man...

Maybe Gib’s was the kind of attitude that sees a man through four years as a foot soldier in the Civil War...

- CONCLUSION

Boatright and others have compared the best of the Gib tales to some of Mark Twain’s work. Like the tales of Twain and other of Gilbert Morgan’s more well-known contemporaries, there are instances of xenophobia, naïvete and cliché here. But at their best, they are imaginative and funny. They have the frankness and playfulness of the storytelling tradition out of which they grew and they remain an essential part of an invaluable record of a time and an industry.

The entire essay is at the journal blog.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home