HERE’S HOW TO BRING GOOD NEW ENERGY JOBS HOME

State Clean Energy Policies Analysis (SCEPA): State Policy and the Pursuit of Renewable Energy Manufacturing

Eric Lantz, Frank Oteri, Suzanne Tegen, and Elizabeth Doris, February 2010 (National Renewable Energy Laboratory)

THE POINT

It’s not JUST the rich economic opportunity in New Energy that matters. And it’s not JUST that the New Energies are a rich source of jobs. It’s also that the New Energies offer a remarkable opportunity to renew the nation’s manufacturing base, JUST when that opportunity is needed the most.

A lot of people find it difficult to understand how so many jobs can be promised by such new industries. That, however, is the point: The New Energy industries are still building their infrastructure and will be building it for decades. It is an infrastructure that will grow from providing 2% of U.S. power to providing probably a third of U.S. power by 2030 and perhaps all of it by the end of this century. Highly capital intensive, 70-to-75% of the cost of a wind project goes to the manufacturing sector, 68% of the total cost of solar power plants goes to equipment and 60-to-64% of the cost of solar photovoltaics is the cost of the modules and inverter. Somebody's got to build all that.

The jobs numbers will boost national labor statistics but the real benefits will go to states and localities. Knowing this, state and local governments are looking to innovate policies especially effective at attracting New Energy manufacturing facility investment. State Clean Energy Policies Analysis (SCEPA): State Policy and the Pursuit of Renewable Energy Manufacturing, from researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), takes a close look at the potential for new manufacturing in the U.S. through 2030 in the solar and wind energy industries and how to best design policies that attract manufacturers.

click to enlarge

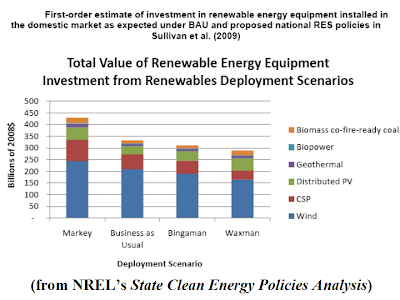

click to enlargeThe researchers estimate the U.S. will invest $14-to-$20 billion per year through 2030 in New Energy hardware. This is based on 2008 DOE projections of what will be involved in the building of enough wind to supply 20% of U.S. power by 2030 as well as 4 domestic New Energy deployment scenarios. The study looks at potential needs for New Energy hardware that would result from pending Renewable Electricity Standards (RESs). It did not assume any specific mandates and it did not assume any price mechanism for greenhouse gas emissions (GhGs). It identified 2 specific uncertainties, (1) how much hardware prices will fall with increasing economies of scale, and (2) how much demand for U.S. New Energy hardware will come from export markets.

The NREL study looks at the factors that determine how locations for new manufacturing facilities are selected and concludes that the essence of a successful strategy to attract new manufacturing facilities is a sustained and broad-based economic development program that (1) builds and promotes “durable assets” (trained workers, a diverse economic base, good infrastructure) and (2) removes the barriers to development (low facility start-up costs, low tax burdens for property and infrastructure).

The paper narrows in on New Energy manufacturing as part of NREL’s State Clean Energy Policies Analysis (SCEPA) project designed to accomplish the larger purpose of working with state officials to help them achieve their overall environmental, economic, and security goals.

The best thing about the long-term, broad-based economic development strategy recommended by NREL is that it is the best thing any state or community can do for itself. Building up strengths and emphasizing human resources are the fundamentals of expanding economic opportunities. Such action is likely to produce some effective kind of economic growth, whether in a New Energy industry or some other industry. Encapsulated in NREL’s sophisticated critical and econometric analysis is a very simple essential message: If you build it, they will come.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeTHE DETAILS

Why states and local communities want New Energy manufacturing facilities: A Renewable Energy Policy Project (REPP) study showed that almost three-fourths of the jobs generated by wind energy development are in the manufacturing sector. A similarly targeted study showed that increasing locally produced turbine hardware from 0% to 35% can increase the lifetime economic impacts of constructing wind projects in Iowa by more than 70%.

As states and localities recognize this potential, they are getting active in efforts to attract New Energy manufacturers. In 2007, only 1 state had a booth at the annual American Wind Energy Association conference. In 2009, 17 states had booths.

More importantly, states and communities are developing policies that will attract facility builders. At least 19 states presently have incentives to lure manufacturers.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeState and local policies are most successful as part of a broad-based economic development strategy that promises the very stability absent from federal programs like the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) that, though presently extended over longer terms, have periodically been withdrawn by Congress and led to severe sectoral recessions.

Effective state and local policies are based on existing resources. They are aimed at developing a skilled workforce. They are supported by an adequate transportation infrastructure. They develop a diverse spectrum of raw material and component suppliers. They are aimed at cutting the cost of manufacturing.

Successful policies also include competitive financial and economic incentive packages that exploit geography and transportation advantages and overcome geography and transportation disadvantages. The goal of effective policies is to make New Energy manufacturing competitive with manufacturers of construction machinery, farm machinery and household appliances.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeThe 4 key parts to attracting New Energy manufacturers:

(1) A multi-faceted and decade-long perspective,

(2) A broad-based economic development strategy,

(3) Industry-specific qualities, and

(4) The addressing of location specific differences.

Critical things needed in an effective comprehensive long-term policy strategy:

(1) State and local infrastructure development. New Energy resources are typically dispersed. Besides being obvious elements of broader economic development, good communication capabilities and transport infrastructure (highways, rail) between the manufacturing facility and the installation attract the New Energy industries.

(2) Education and workforce training. Institutions that produce trained labor and knowledgeable professionals mean a skilled and capable pool of talent to build New Energy. States and localities can get ahead by starting skills centers, and folding New Energy training into community college-level programs. At the University level, R&D programs lead to New Energy spin-offs that typically move to adjacent communities.

click to enlarge

click to enlarge(3) Direct outreach and marketing. States and localities should consider opening offices in and paying state visits to countries where there are New Energy companies they could feasibly interest in building manufacturing facilities.

(4) Community development and quality of life programs. New Energy companies may choose to build manufacturing facilities in places that offer a superior quality of life. Pre-investment in public services, parks and recreation, cultural outlets and other things that imply a high quality of life makes states and localities more likely to win investment.

(5) A predictable regulatory and governing environment and limited entry barriers. Keeping the effort of getting started (plan approvals, permits, transition details) attracts investors. Laws and policies that set long-term regulations, requirements, processes and opportunities make doing business easier.

(6) Provision of fiscal and financial incentives. Lower costs are absolutley necessary to meet the competition from other states and localities. They do not, studies show, offset the absence of other parts in a comprehensive program. The ideal programs couple financial incentives with a broad-based, farsighted economic development program.

(7) Detailed market and resource analysis. States and localities will get more investment for their effort by doing their homework and identifying the New Energy companies best matched to their resources, talents and environment.

(8) Advancement of New Energy markets. State and local leaders should create policies that increase New Energy consumption both at the local and national levels, especially focusing on consumption of the New Energy products they seek to manufacture in their communities.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeTraditional incentives such as tax assistance, long-term and short-term loans, job training funds, and physical infrastructure assistance, lack a broad-based strategy and leave out elements of such a comprehensive program and have not proven effective when subjected to careful scrutiny.

When economists looked at the power of financial incentives alone to explain the location of direct investments, their impact was revealed to be limited. A study of labor subsidies, capital subsidies, and foreign trade zones showed they were not conclusively determinative in the siting in the U.S. of foreign direct investment.

More relevantly, econometric analysis showed that financial incentives do not actually generate jobs in underdeveloped or depressed areas. Similarly, a historical analysis showed that when competition between states for auto industry facilities drove up financial incentives, as competition is presently driving up financial incentives for New Energy facilities, the actual amount of direct investment was not affected.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeThough New Energy industry decision makers say financial incentives alone are inadequate to justify a decision to place a manufacturing facility, they do keep states and localities competitive and are effective tools through which larger, more comprehensive programs can be marketed.

The current economic downturn has seen continued growth in the New Energies as the result of 3 federal policies that correct the longstanding uncertainty spawned by Washington, D.C., (1) the extension for 8 years of the ITC, (2) the extension for 3 years of the PTC, and the provision of a variety of flexibilities in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to make the ITC, the PTC and the development of new manufacturing facilities more viable long-term despite the absence of ready credit.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeFinancial incentives include property tax rebates, income tax credits, grants, loans, sales tax exemptions and, sometimes, infrastructure improvements. The key to policies governing financial incentives is to calibrate them accurately. If they are too low, manufacturers will go elsewhere. If they are too high, states and localities will lose money.

Such policies can be used to encourage siting a facility in a way the state or locality prefers. The incentives and other infrastructure improvements can be managed so that manufacturers build where it is mutually advantageous for the state or locality and the manufacturer: If the manufacturer chooses the state or locality’s preferred site, the financial incentives would be greater.

Influencing the building of manufacturing facilities in the places that suit the state or community is even more successful when it is part of a community or state development policy that pre-determines where energy and communication infrastructure and transport routes go.

Perhaps, therefore, it is more than "if you build it, they will come." Perhaps it is how you build it, how well you plan it before you build it, and how much you are willing to put on the table to get them to come and take a look at what you have built.

click to enlarge

click to enlargeQUOTES

- From the study: “Given the long-term outlook for renewables, the United States is an attractive manufacturing location for firms looking to serve the North American renewable energy market. However, in today’s economy, the desire for renewable energy manufacturing jobs could quickly exceed the market demand for renewable energy products. Competition among states for a finite pool of renewable energy manufacturing investment can benefit and challenge state policymakers targeting renewable energy manufacturing opportunities. On one hand, competition can drive states to invest directly in infrastructure and human capital in order to attract both foreign and domestic investment. On the other hand, competition can drive up the financial and fiscal incentives that local governments feel they need to attract manufacturers. Data from the automotive industry indicate that the public investment per job increased by a factor of more than 40 between 1980 and 1997…However, past a point, incentives grow so large they no longer represent a net benefit for their provider. Furthermore, to the extent that increased incentives shift funds from investment in infrastructure and workforce development, relying on incentives to attract new manufacturers may actually diminish a state’s ability to maintain or develop its fundamental economic assets…”

click to enlarge

click to enlarge- From the report: “Renewable energy markets in the United States are growing rapidly, and the long-term outlook for the industry is positive. In addition, the economic development impacts of renewable energy are notable even without considering the impacts of U.S.-based manufacturing. However, a great deal of renewable energy job generation will occur outside the United States if the country continues to import much of its renewable energy equipment…”

click to enlarge

click to enlarge- From the report: “Marketing strategies for states seeking to attract manufacturers may be best served by multi-faceted strategies that allow them to compete in terms of financial incentives but are more focused on differentiating themselves by leveraging and strengthening durable assets. Policy measures designed with this goal in mind emphasize broad-based infrastructure development, industry-specific worker training, progressive renewable energy deployment policies, and a stable regulatory environment, as well as investment in public education and research, community development, and quality of life factors. A long-term broad based approach such as that outlined here takes time to reveal its value. Nevertheless, it is more likely to yield a sustainable outcome…”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home