Monday Study – Utility Financial Viability At Risk

Hidden Risks of US Utilities

Management, February 2021 (Lazard asset Management)

The Lazard Global Listed Infrastructure strategy currently has low exposure to the US utility sector. This low weight is in direct contrast with listed infrastructure indices and many active managers in this asset class. While many US utilities are high quality natural monopoly assets, we are unable to find value in the sector today. Current valuations imply that the rare combination of low interest rates, generous allowed returns, and solid rate base growth will continue indefinitely. Although this situation has persisted for several years, we believe the risks of a reversal are rising.

US Utility Earnings

US utilities that are in our preferred infrastructure universe transmit essential commodities like gas, electricity, and water. They are not the power generators or energy retailers that sell to the consumer, rather they own network assets. Utilities that deliver these essential services earn a return on invested capital as determined by a regulator while their fuel, operational and maintenance costs are generally passed-through directly to the consumer.

In the US, each state has its own regulatory agency and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission regulates interstate transmission assets. As a result, there is a degree of variability in the utilities’ authorised rate of return earned on invested capital. Utilities invest in their networks, maintaining and extending these assets, and improving their efficiency and safety, as well as building new assets for, say, transmission of renewable energy. The more the utility can invest in its infrastructure, the more revenue it can generate.

The Current Situation

US utilities have enjoyed a widening spread over the risk-free rate since the early 1980s, as allowed returns have declined less than bond yields, a trend that accelerated in the ultra-low rate environment of the last decade (Exhibit 1). This has allowed the utilities to earn a premium to global peers, whose returns are usually linked via formula to the risk-free rate.

Exhibit 2 highlights the experience of regulated UK water utilities, where allowed returns have tracked lower alongside the cost of debt.

While US utilities’ allowed returns are typically not linked to interest rates by any formula, we expect that regulators will not allow them to over-earn forever, so our long-term projections assume a lower cost of capital spread than what is currently allowed.

At the same time as US utilities have been earning quite generous returns on rate base, the rate base has been growing consistently (Exhibit 3)

Some of the areas of network and generation investment add to the rate base, and at the same time reduce operations and maintenance expense (O&M) which is a pass-through cost to customers. These areas of investment include:

• Installing advanced metering infrastructure, which dramatically improves workforce efficiency.

• Phasing out coal plants in favour of gas and renewable generation (renewable assets add to the rate base and eliminate the variable fossil fuel costs).

• Retrofitting existing generation assets to reduce emissions.

• Building out transmission networks to interconnect regions.

As a result, while rate base growth has been high, the reduction in O&M has helped offset the impact on customer bills.

Other areas of capital expenditure, which are critical, have also added to rate base growth, including:

• Safety and reliability investment (e.g., the federally mandated pipeline replacement project to reduce leaks and wildfire risk by hardening the network).

• Grid investment to keep pace with the widespread adoption of innovative technologies (e.g., electric vehicles).

• Network investment to accommodate the addition of renewables (e.g., household solar)

Can rate base growth persist at such high rates?

While US utilities’ projections of rate base growth over the next five years suggests that rate base growth levels will be similar to history, there is significant variability within the broader cohort of US utilities. The key question for investors, then, is whether the combination of extreme low interest rates, high allowed returns, and rate base growth will continue.

In our view, at the valuations where these assets are trading, any breakdown in this perfect set of circumstances could see a material de-rating.

US electricity prices have not risen in real terms over the last decade. In fact, they have regressed slightly, while personal income has grown (Exhibit 4). Customer bills have been largely flat with increases in capital investment (net plant) being offset by various cost savings, primarily in energy costs—the price of natural gas has fallen significantly (Exhibit 5).

The utilities have had the additional advantage of macroeconomic tailwinds over the past decade:

• The decline in interest rates, reducing interest expense.

• The reduction in the federal corporate tax rate

• The gradual ongoing refunds to customers of over-collected tax (deferred tax liabilities)—this liability materialized at the time of the corporate tax rate cut.

• Federal tax credits arising from the construction and electricity production of renewables.

• Network expansion for customer growth (for some utilities, but not all).

Although these tailwinds should be to some extent sustainable, we think they are unlikely to be as strong in the future as they have been in the past. Ultimately, we think that ongoing high levels of capital expenditure (and rate base growth) will flow through to customer utility bills, and regulators will need to consider curbing rate base growth or lowering utilities’ allowed rate of return. Neither option is positive for US utility valuations.

Above and beyond industry-specific risks looms the prospect of higher interest rates. Should the downward rate trend of the past 30 years start to reverse, it could add a further obstacle to US utility valuations. Such a scenario would, we believe, automatically start to correct the over-earning issue, by reducing the spread between allowed returns and interest rates. US regulators would probably avoid lifting allowed returns in response, likely keeping returns flat and letting the spread return to more normal levels. In simple terms, the discount rate will rise with no offsetting change in earnings - leading to a decline in values.

Valuations

We think these risks are heightened because US regulated utilities are currently trading significantly above their long-term averages (Exhibit 6). US utilities are the single biggest sector in global infrastructure indices.

Their performance consequently makes up a major portion of the returns from passive infrastructure investments and active portfolios with large positions in US utilities.

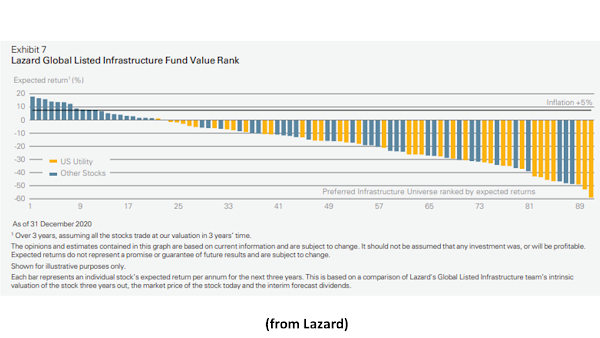

Our internal value rank highlights the challenges facing the sector. In Exhibit 7, each bar represents the expected annualised return over three years, for each stock in our Preferred Infrastructure universe, based on the assumption that all stocks will trade at our valuation in three-years’ time. As the chart shows, we see potential negative returns over the next three years for US utilities. Only one US utility has positive expected returns over the period.

Conclusion

Utilities’ appeal of stable and growing earnings that are not linked to the economic cycle is obvious, but investors need to be mindful of the risks. US regulated utilities have benefited from a confluence of circumstances which has enabled them to enjoy sustained high rates of rate base growth and allowed returns well above their cost of capital, all without raising prices to their customers. We do not believe these conditions can last forever and question whether the market is pricing the risks properly. Accordingly, the Lazard Global Listed Infrastructure strategy has low exposure to this sector.

click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home