TODAY’S STUDY: Key Numbers On Energy Storage As A Grid Support

Modernizing Minnesota’s Grid; An Economic Analysis of Energy Storage Options

July 11, 2017 (University of Minnesota Energy Transition Lab, Strategen Consulting, and Vibrant Clean Energy)

Executive Summary

Overview

Stakeholders in Minnesota’s power sector convened in two workshops held in September 2016 and January 2017 to discuss a statewide strategy for energy storage deployment.

The first workshop helped identify areas for more in-depth analysis. Preliminary results from this analysis and from real-world case studies were presented at the second workshop and used to guide a broader discussion around recommended next steps. The workshops and analysis made the following key findings: • Under an optimal set of future energy resource investments and operating practices, the leastcost solutions included energy storage.

• Energy storage can be a cost-effective means to help Minnesota meet its state greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals.

• The deployment of storage in Minnesota was projected to increase the use of low-cost renewable energy generation dispatched in MISO and to reduce the need for expensive transmission investments.

• Historically, utilities have used gas combustion turbines to meet peak demand. As storage becomes more cost-effective, it will compete with and displace new gas combustion peaking plants (peakers).

• Compared to a simple-cycle gas-fired peaking plant, storage was more cost-effective at meeting Minnesota’s capacity needs beyond 2022.

• Solar + storage was found to be more cost-effective than a peaking plant today, primarily because of the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and additional environmental benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

• At least one distribution cooperative in Minnesota is already pursuing deployment of a solar + storage facility. Through a series of facilitated discussions, workshop participants generated a set of recommended next steps for immediate action.

• Lead study tours to educate Minnesota stakeholders about existing storage projects.

• Develop a proposal to deploy commercially significant energy storage pilot projects.

• Modify the existing Community Solar Gardens program to facilitate solar + storage projects. In addition, participants recommended the following steps that are ongoing or longer-term and can be pursued in parallel with the immediate actions.

• Direct energy producers to conduct future capacity additions through all-source procurement processes.

• Update modeling tools used by utilities and regulators for resource planning to better capture the costs and benefits of storage.

• Identify utility cost recovery mechanisms for new energy storage investments.

• Develop MISO rules that appropriately consider energy storage as a capacity and grid resource.

• Conduct an assessment to link storage to Minnesota’s system needs.

• Develop innovative retail rate designs that would support a greater deployment of energy storage. • Educate state policymakers through meetings and briefing materials.

• Identify opportunities for large electric customers to host storage projects.

• Host technical conferences for planners, grid operators, and utilities. In addition, workshop attendees suggested system analysis to identify high-impact locations for storage system benefits.

Background

Minnesota is a leading state in clean energy production and grid modernization. Over the last decade, the renewable portion of Minnesota’s electricity mix has grown from 7% to over 21%.2 The state is also a leader in encouraging new energy technologies from a policy perspective, exemplified by its Grid Modernization and Distribution Planning Law (H.F.3, 2015) and related Public Utilities Commission proceedings (Docket #15-556).

Despite these efforts to date, Minnesota has deployed relatively little advanced energy storage technology and has not included storage in its integrated resource planning efforts. At the same time, other states are experiencing a variety of storage benefits. In California, for instance, utilities have deployed energy storage to provide necessary generation capacity to critical population areas such as the Los Angeles basin. In the PJM market, storage projects have provided ultrafast grid balancing services (fast frequency regulation). In Hawaii, storage integrated with solar PV has provided a cheaper alternative to expensive oil-burning power. In light of these success stories and other recent changes in the storage market, a group of Minnesota energy experts participated in a workshop series to explore the future role of energy storage in the state. This report describes the workshop’s process and its findings, details the supporting analysis that was presented at the meetings, and presents ideas for appropriate next steps…

In the fall of 2016, the University of Minnesota’s Energy Transition Lab (ETL) launched an energy storage planning process with a diverse set of Minnesota energy sector stakeholders, with support from the Energy Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, the Minneapolis Foundation, AES Energy Storage, General Electric, Next Era Energy Resources, Mortenson Construction, and Great River Energy. Additionally, the Carolyn Foundation provided support for the preparation and dissemination of this report. The primary objective was to explore whether and how energy storage could be used to help Minnesota achieve its energy policy goals while enabling greater system efficiency, resiliency, and affordability. All workshop participants were encouraged to come to the table with an open mind and no expectation of a particular outcome…

Minnesota Energy Storage Strategy Stakeholder-Recommended Priority Actions

While some states are beginning to deploy grid connected energy storage on a large scale,15 Minnesota utilities and regulators have been hesitant to deploy energy storage widely because of concerns of cost effectiveness, cost recovery, and lack of operational experience with the asset class in general. Modeling data and peer utilities’ experiences can help to identify favorable use cases for Minnesota. However, load-serving entities and regulators eventually need operational experience to link energy storage capabilities to Minnesota’s unique grid needs. While the first deployment of any new technology may entail operational and institutional costs—as energy producers, grid operators, and regulatory agencies adapt to the new development—these costs are often one-off and enable future, lower-cost deployment of the technology. In short, there is simply no substitute for ‘learning by doing’.

Generally, most workshop participants agreed that finding opportunities to deploy solar + storage today was a low risk, “least-regrets” strategy in at least two instances:

1 - on the utility side, as an alternative to new gas peaking capacity, which was found capable of delivering net benefits and achieving nearterm GHG emissions reductions; and

2 – on the customer side, as a mechanism for Generation & Transmission (G&T) utility customers (e.g. rural cooperatives) to reduce their peak load and avoid demand charges, yielding system cost savings.

Because the federal Investment Tax Credit for solar projects is scheduled to phase out over the next four years, a number of stakeholders agreed that solar + storage projects should be identified and deployed in the very near term. A number of stakeholders also expressed that it would be a sensible next step to move forward with a limited, yet commercially significant solar + storage procurement. This would likely yield significant learning benefits for Minnesota’s energy sector and generate lessons for future integrated resource planning efforts. These lessons could outweigh potential near term costs and risks that might arise.

Recommended next steps for immediate action

To help realize these benefits, based on the system level modeling and individual resource cost effectiveness modeling, and in the spirit of ‘learning by doing’, the stakeholder group identified a series of actions that could be undertaken in MN to further advance energy storage as a viable option in MN’s electric power sector planning toolkit. Several of these actions were identified as discrete, near-term steps while others would be longer-term or ongoing, and complementary to the immediate actions.

1. Host a utility-focused technical conference (or series of conferences) to advance thinking on energy storage to support planning, grid operations, interconnection, measurement and verification and utility training. This conference could also address at a high level alternative contracting mechanisms, including those for utility-owned, third party-owned and aggregated solutions. Recommended leaders for this effort: ETL/MESA, Minnesota utilities and the PUC

2. Identify and clarify potential utility cost recovery mechanisms for prudent energy storage investments. This is critical, as cost recovery risk is a key barrier preventing investor owned utilities from investing in energy storage projects. At the same time, criteria should be established for qualifying pilot projects. Recommended lead: PUC

3. Work with utilities to develop and propose one or more energy storage pilot projects to the PUC with broad stakeholder support. A necessary component of this type of proposal would be an agreed-upon mechanism for cost recovery to be approved by the PUC.

The steps would include the following:

a. Identify particular system needs and locations that could be effectively met with energy storage.

b. Propose a commercial scale Minnesota energy storage procurement process to demonstrate energy storage as a viable alternative to new gas peakers or other appropriate use cases. Such a procurement would help discover current price data and help identify best practices for storage project development (e.g. planning, siting, contracting, permitting, interconnection, etc.).

c. Partner with universities to conduct research and analysis of power control systems, operational integration, economic performance, and other areas of learning, making them explicit goals of these initial pilot projects. This may result in University and other expert partner white papers. These additional research objectives could be optional if they are found to be cost prohibitive.

4. Because of superior cost effectiveness and lower GHG emissions, solar + storage should be prioritized near term. For example, the PUC could authorize 20 MW of utility owned and 20MW of third party owned (either centralized or aggregated behind the meter) energy storage and or energy storage + solar procurement pilots, to complement the learning from Connexus’ solar + storage procurement underway. Engaging in a commercially significant pilot will shed light on key implementation barriers and issues very efficiently. Recommended lead: PUC, Minnesota utilities

5. Direct future capacity additions to be conducted through technology neutral all-source procurements. This would specify the need in terms of its capabilities, rather than its technology or generation type, and allow all resource types (including energy storage and energy storage + solar, as well as other technologies) to participate. The process and methodology for evaluating the all-source procurement should be established well in advance of its implementation. Recommended lead: Utilities; PUC

6. Update modeling tools used in integrated resource planning process (i.e. Strategist) to allow for appropriate treatment and evaluation of energy storage as a potential resource. Recommended lead: DOC, PUC, utilities.

7. Craft MISO rules, processes and products for energy storage participation. This should encompass not only standalone energy storage, but also behind the meter aggregated energy storage solutions as well as storage coupled with wind and solar. Recommended lead for this effort: MISO Develop innovative rate designs to allow customers to access storage benefits.

8. Conduct an assessment to link storage to Minnesota’s system needs.

9. Develop innovative retail rate designs that would support a greater deployment of energy storage. Recommended lead: utilities, PUC.

10. Lead a study tour of MN stakeholders to existing grid connected and customer-sited energy storage installations. Recommended lead: ETL/MESA

11. Conduct outreach and education for state policymakers. This could include meetings with both state legislators and regulators. Ideally, it would include development of short briefing materials to summarize use cases, opportunities, and challenges for energy storage in Minnesota. Recommended lead: ETL/MESA

12. Engage large customers to identify potential project hosting opportunities. Stakeholders would approach large potential host sites (e.g. large commercial and industrial customers, distribution centers, etc.) to identify potential value propositions. Recommended leads: MN Sustainable Growth Coalition, ETL/MESA.

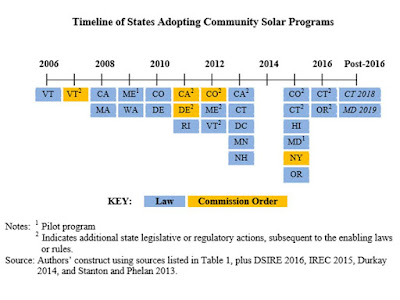

13. Refine the existing Community Solar Gardens program to include a peak time option for energy storage. This would create a minor modification to existing program structure and methodology to allow for a solar + storage option (credit rate calculation would reflect the additional value of storage). Recommended lead: ETL/MESA, AG’s Office.

Other recommendations highly rated by workshop attendees included innovative rate designs to allow customers to access storage benefits and system analysis to identify high-impact locations for storage system benefits.

Limitations and Opportunities for Further Analysis

The project team’s analysis was limited in scope due to budget and time constraints. As with all modeling exercises, the quality and usefulness of the results are a direct function of the underlying assumptions and inputs. The following additional analyses could be undertaken to build on this initial work and further inform the path forward. However, it should be noted that there is still no substitute for ‘learning by doing’ and these additional modeling suggestions are not intended to be prerequisites for implementing the action recommendations developed by the stakeholders in this process.

1. Additional system optimization scenarios:

a. Natural gas scarcity and price spike scenarios

b. Storage with longer than four-hour duration (including flow battery technologies)

c. Additional years of weather data

d. More cost trajectories for technology inputs

e. Future scenarios with more GHG reduction

f. Future load scenarios including electric vehicle charging and various heating/cooling and thermal storage scenarios

g. More transmission coordination among MISO, SPP, and PJM

h. Multiple hub heights for wind generators

2. Individual resource use case cost-effectiveness analysis that could benefit from additional sensitivity analyses:

a. Locational benefits: identification of specific locations in Minnesota’s distribution system that are constrained or experiencing other issues energy storage can address. For example, the integration of energy storage with existing fossil generation could immediately improve local air emissions.

b. Installation costs: MISO values used in this study for peaker costs may not be representative of some utilities in the state

c. Frequency regulation: recent experience suggests that frequency regulation values can differ from initial modeling predictions

d. Comparison to or combination with other capacity alternatives such as demand response

e. GHG emissions: additional research into local drivers of marginal generation resources

click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge

Plug-in Hybrids, The Cars That Will Recharge America

Plug-in Hybrids, The Cars That Will Recharge America Oil On The Brain

Oil On The Brain